Disease Information

History and background of WM

WM is a rare, indolent B-cell lymphoma characterised by the overproduction of immunoglobulins, predominantly immunoglobulin M (IgM), by malignant antibody-secreting cells.1,2 Clinical features may be related to overall disease burden, such as anaemia, or may be directly attributable to the IgM paraprotein.1 It is frequently preceded by IgM monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS).1 MGUS is defined by having all of the following criteria:1

- The presence of an IgM paraprotein of less than 30 g/L

- Absence of a lymphoplasmacytic bone marrow infiltration

- Absence of signs or symptoms such as occur in WM itself

The rate of transformation for an individual with IgM MGUS to WM is approximately 1%–2% per year.1 Not all patients with MGUS go on to develop WM.1

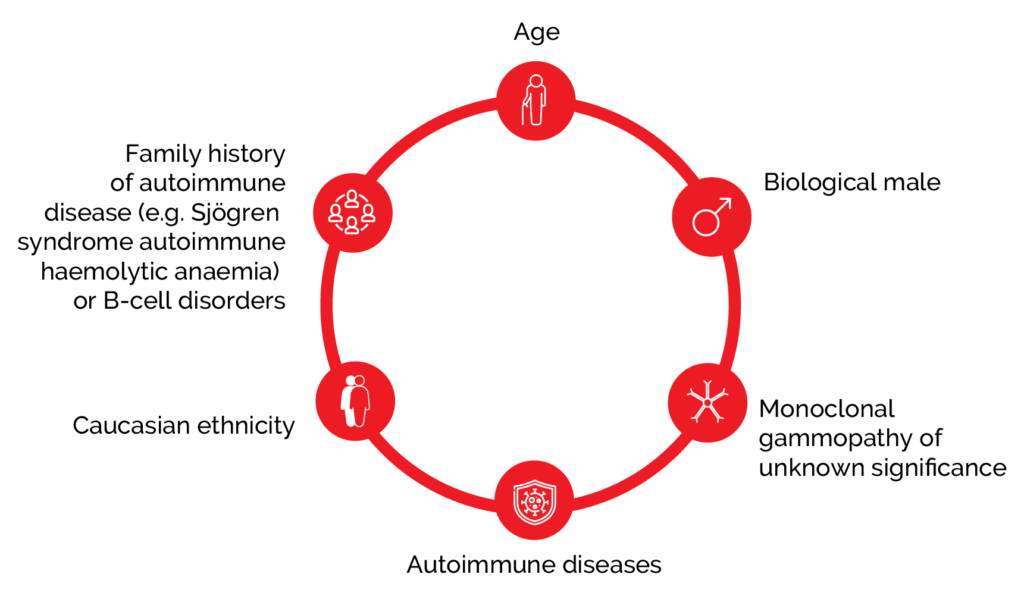

Aetiology

WM is more common in the elderly, Caucasians, and males.1 There is an increased risk of WM when there is a personal or family history of autoimmune (Sjögren syndrome, autoimmune haemolytic anaemia), inflammatory and infective disorders, or other B-cell disorders, but screening is not recommended due to low absolute risk.1 WM is associated with genetic mutations and around 90% of patients with WM harbour a mutation in the MYD88 gene, which appears to be central to the disease pathogenesis.1

Figure 1. Risk factors for developing WM include age, disease, and family history.1

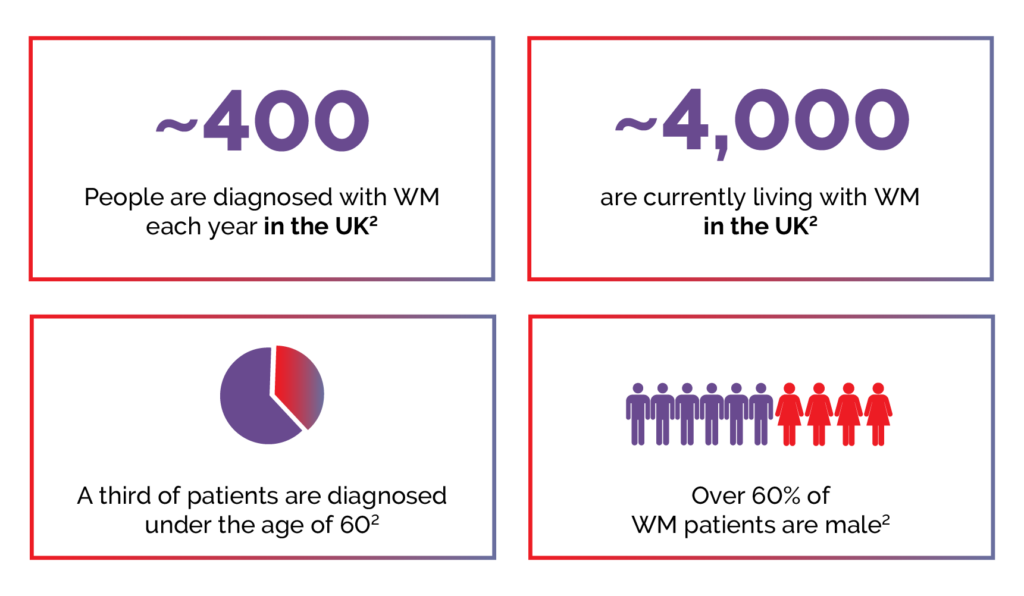

Epidemiology

WM is rare, with approximately 400 cases diagnosed in the United Kingdom each year, and about 4000 people are currently living with the condition.2

Figure 2. Key WM statistics.2

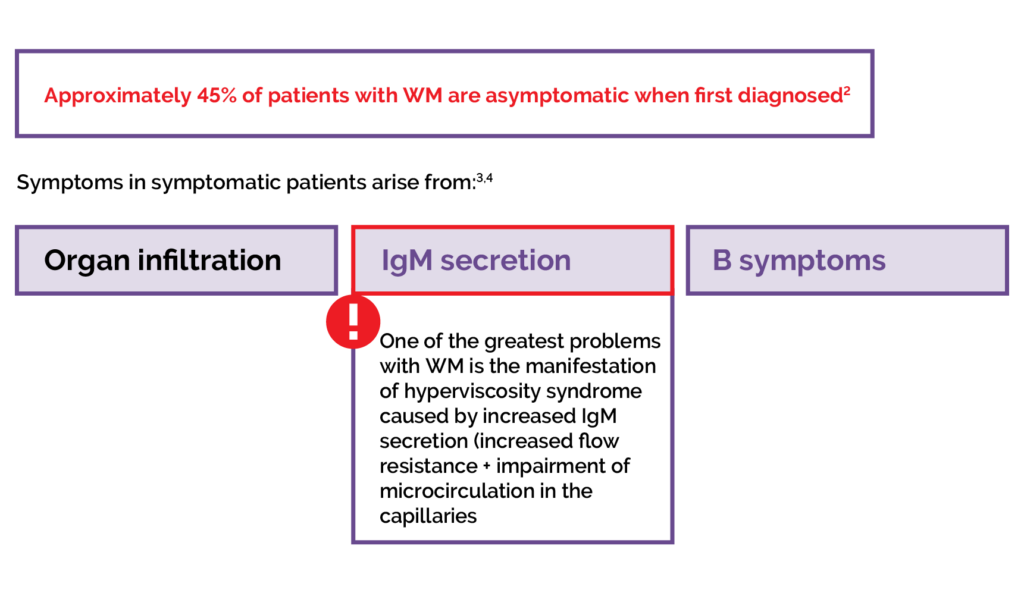

Symptoms

WM often develops over a long period of time,2 and is characterised by:1

- Bone marrow infiltration by lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (LPL)

AND

- Immunoglobulin IgM monoclonal gammopathy

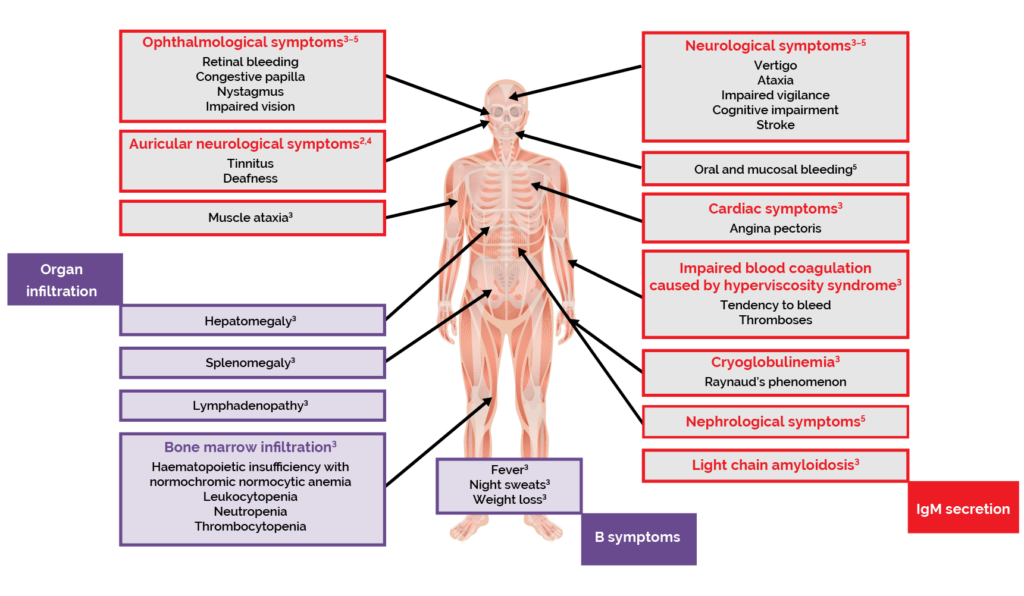

The clinical features of WM are related to the defining aspects of the disease.1,2 Infiltration of the bone marrow and other organs by LPL cells interrupts the production of blood cells.1–3 This results in lymphoma-related features such as anaemia, and symptoms including fatigue, weakness, and shortness of breath.1–3 Patients with WM can also experience ‘B symptoms’, commonly associated with lymphomas, including fever, night sweats and weight loss.2,3

Excessive production of IgM can cause hyperviscosity of the blood, which is a haematological emergency.1,2 Symptoms of hyperviscosity syndrome include blood coagulation disorders, neurological symptoms such as dizziness and ataxia, visual disturbances, and cardiac symptoms.3

Other complications related to the presence of excessive IgM paraproteins include peripheral neuropathy, cold-agglutinin disease and cryoglobulinaemia.2,3

Figure 3. The cause of symptoms in WM.2–4

Figure 4. Clinical features and symptoms of WM.2–5

Investigations and diagnosis

Investigations for suspected WM include history and physical exam, laboratory tests, bone marrow aspiration and biopsy, flow cytometry and/or immunohistochemical analysis for determination of immunophenotype, molecular testing for MYD88 and CXCR4 mutations, and imaging.1,6

Table 1. Useful investigations in patients with suspected or established WM.1

| Clinical indication | Suspected complication | Bendamustine + rituximab (n=227†) |

|---|---|---|

| At diagnosis | – FBC – Urea and creatinine – Liver function tests – LDH – β2 microglobulin – Hepatitis B, C, HIV status – Serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation – Quantification of IgM by densitometry – Quantification of IgG and IgA – SFLC – Plasma viscosity – Ophthalmic examination for signs of hyperviscosity – Bone marrow aspirate and trephine biopsy · Flow cytometry • Genetic analysis for MYD88 and consider for CXCR4 and TP53 • Congo red stain if amyloid suspected | |

| Prior to treatment | – Baseline CT neck chest abdomen and pelvis if symptomatic – Repeat paraprotein quantification – Virology (hepatitis B, C, HIV) – Consider bone marrow aspirate and trephine biopsy | |

| Anaemia | Haematinics, haemolysis screen (reticulocyte count, LDH, haptoglobin, bilirubin), DAT | |

| Bleeding | – Hyperviscosity – Acquired VWD – Amyloidosis (acquired factor deficiency) | – Paraprotein quantification – Plasma viscosity – Coagulation studies – VWD screen – Factor assays – SFLC |

| Lymphocytosis | – Flow cytometry to confirm if PB involvement | |

| Neuropathy | – Peripheral neuropathy – Cryoglobulinaemia – Amyloidosis – POEMS | – Anti-MAG titre – Anti-ganglioside antibody – Additional anti-neuronal antibodies in discussion with peripheral nerve specialist – Cryoglobulin – SFLC – VEGF – Nerve conduction studies – Lumbar puncture for CSF analysis • Cytology • Protein • Flow cytometry • Molecular analysis for MYD88 and PCR for IgH rearrangement – Nerve biopsy |

| Skin rash/ purpura/ Raynaud phenomenon/ ulceration | – CAD – Cryoglobulinaemia – Schnitzler’s syndrome | – DAT – Haemolysis screen – Cryoglobulins – Skin biopsy |

| Renal impairment | – Cryoglobulinaemia – Amyloidosis | – Cryoglobulins – 24-h urine protein – SFLC – Renal biopsy |

| Suspected amyloidosis | – SFLC – Biopsy of involved tissue – Congo red stain for amyloid – SAP scan – Assessment of organ function • Echocardiogram/ cardiac MRI troponin/pro-BNP • 24-hr urine protein • Urine albumin:creatinine ratio | |

| Suspected high grade transformation | – PET-CT – LDH – Biopsy of suspected area of transformation | |

| Suspected Bing–Neel syndrome | – Brain and whole-spine MRI with gadolinium contrast (if renal impairment consult cardiologist) – Lumbar puncture for CSF • Cytology • Protein • Flow cytometry • Molecular analysis for MYD88 and PCR for IgH rearrangement |